Last summer, I was amazed by the accuracy of the acoustics on the hake survey. We could easily identify a huge school of hake, line up the ship to put the net in the water at the right depth and coordinates, and then (with a few exceptions) land a net full of almost entirely hake.

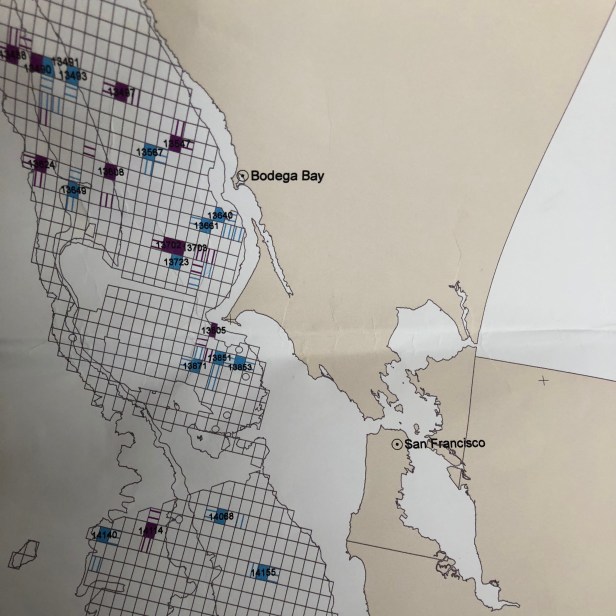

The US West Coast groundfish bottom trawl survey takes place in a similar area offshore from Canada to Mexico, on the continental shelf and slope from depths of 55 to 1280 meters (180 to 4200 feet). Instead of surveying transects, this entire study area is divided into a grid of stations, 1.5 by 2 nautical miles in size. Each survey vessel visits a randomly selected subset of these stations.

On the groundfish survey we’re not fishing only for marketable species, as a commercial fishing operation would. We’re studying the entire habitat. That means fishing in random locations and sorting, weighing, counting, and taking samples from everything that comes up in the net. My previous post about bottom trawling describes the fishing method in more detail, and helps to explain why our catch looks like it does: multiple species of fish, plus crabs, anemones, sea stars, and some other surprises!

We might complete four or five stations each day, depending on the distance between stations, the weather, and the contents of each catch. For a scientist on this survey, a typical day might go something like this:

- Wake up early to the sound of the hydraulic winches. Wonder how far offshore we are, because that will determine if there’s time to sleep a little longer, or if you need to get up and go straight to work. In deep water offshore, the net might take a couple of hours to reach the bottom and get back on deck. Shallow tows are a lot faster.

- Drink coffee and eat something simple, if there’s time.

- Get ready to work outside. Put on rubber boots, rubber pants, and rubber gloves. Every time. If it’s windy or waves are big, definitely wear a rubber jacket too.

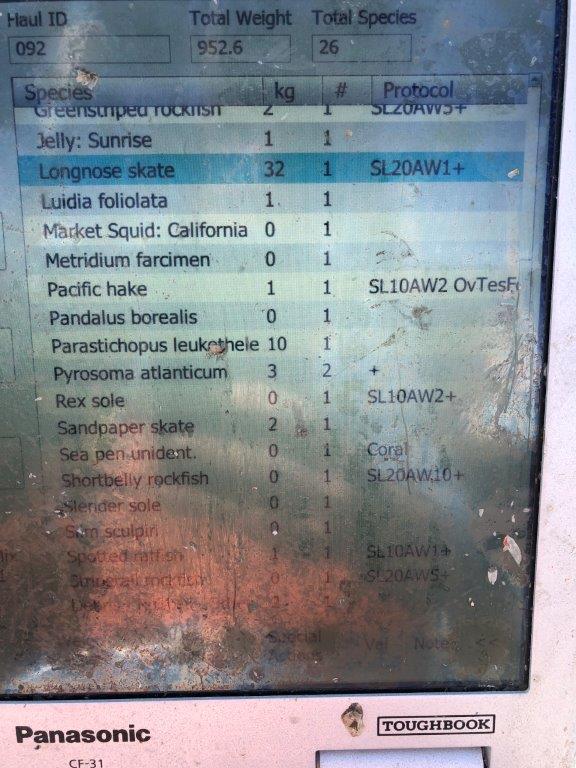

- Start sorting through a big slimy pile of whatever’s in the net. Maybe it’s cool looking fish and crabs. Maybe it’s gross urchins, sea cucumbers, or jellyfish. Maybe there are hagfish and their slime. Maybe it’s a big mix of everything. Sort anything and everything into baskets and tubs by species. Weigh things. Count things.

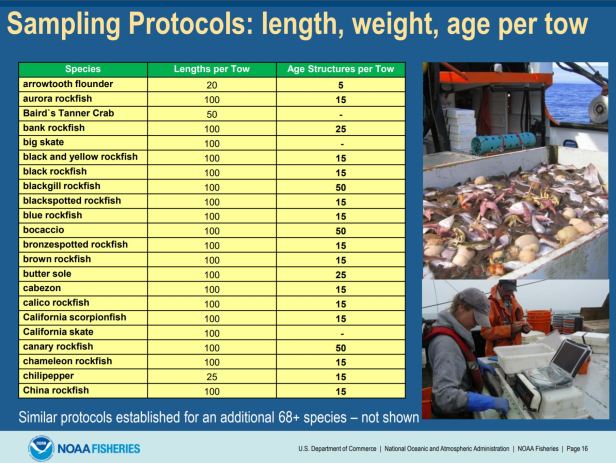

- Take subsamples (a number individual fish selected from a few hundred kilograms of a species of concern, for example) and sort those by sex, measure and weigh individuals. Subsample again (select a few from the original subsample, as shown in the sample protocol example below) and extract, label, and preserve otoliths, fin clips, dorsal spines, internal organs, or vertebrae from any species being studied in more detail. Maybe put some whole specimens in the freezer for further research.

- Clean up the mess. Hose off the table, baskets, scales, the deck, and yourself.

- While the scientists were doing steps 4 through 6, someone on the crew probably cooked breakfast. (Or lunch, or dinner.) Take off your rubber outer layer. Go inside and eat something, usually accompanied by the sound of the winches hauling back the next tow.

- Repeat steps 3 through 7 until sunset.

- Sleep.

- Tomorrow, start over at step 1.

Wait, did I forget to mention taking a shower after a full day of slimy, fishy work? Nope! I didn’t forget! As I explained in my description of the Last Straw, there’s only one small shower/head combo, shared by all seven people on board… I usually skipped the shower and went straight to sleep.

I also didn’t mention taking lots of photos every day. It’s just not that easy to get your hands on a camera when you’re in foul weather gear from head to toe, possibly covered in slime and seawater, and sometimes working outside in crazy weather. (More about the weather in a future post!) I knew I’d be writing about this experience and I can’t imagine trying to describe it without photos, so sometimes I stashed my phone in a fanny pack under my giant rubber pants to document as much as I could! For you! You’re welcome!

So many baskets…

So many subsamples…

We caught a few unique things too, which we didn’t see every day.

Of course there were some big fish, too. Especially interesting were the larger rockfish, some of which have been overfished and will still take many years to completely recover.

After sorting the catch by species, there was still a lot of work to do, recording details about individuals and storing samples for analysis in laboratories on land.

The data we collected contributes to stock assessments for multiple groundfish species. Some species are seriously threatened, like yelloweye, which can live more than 100 years, and cowcod, which are among the largest rockfish, prized by sport fishermen and now heavily restricted. Survey data also help to monitor changes in the range of species, and changes in habitat and ocean conditions.

For more detail about findings from the groundfish survey, check out this NOAA presentation which summarizes data from past surveys.