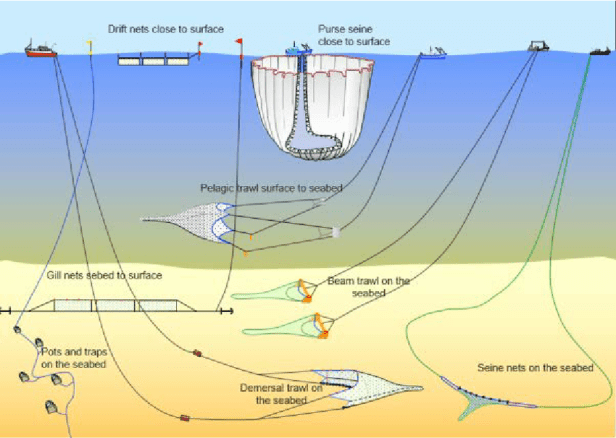

Compared to other common commercial fishing methods, bottom trawling is one of the most damaging.

In contrast to midwater (pelagic) trawling, which can target a single species of fish in the water column, bottom (demersal) trawling often unintentionally catches multiple species in addition to marketable fish, and drags heavy trawl doors and weighted nets along the sea floor which can leave behind lasting scour marks. The environmental impacts of bottom trawling can be serious:

- habitat destruction – damage to features of the sea floor that serve as habitat

- collateral mortality – damage to corals, sponges, seagrasses and other living things

- economic bycatch – species discarded because they’re not valuable or marketable

- regulatory bycatch – species discarded based on size limits, catch allocations, or seasons

The Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch Program, which publishes a consumer guide and app to help identify sustainable seafood choices anywhere in the United States, created this animated explanation of bottom trawling:

By (1) limiting areas where bottom trawling is allowed, (2) modifying fishing gear to reduce or eliminate bycatch, and (3) enforcing science-based limits on both targeted and discarded species, it has been possible for several groundfish species to recover from near collapse in 2000 and earn sustainability certifications from organizations like the Marine Stewardship Council. Some of the species we caught and studied on the survey—rockfish, sablefish, sanddab, and sole—appear on the Seafood Watch US West Coast Best Choices list.

Several international conservation organizations seek to protect sensitive or pristine habitats from bottom trawling. Some countries like the United States and the European Union have substantially limited areas where bottom trawling is allowed within their own jurisdictions. Others, like Palau and New Zealand, would also support an international ban on bottom trawling, but it remains unregulated in international waters.

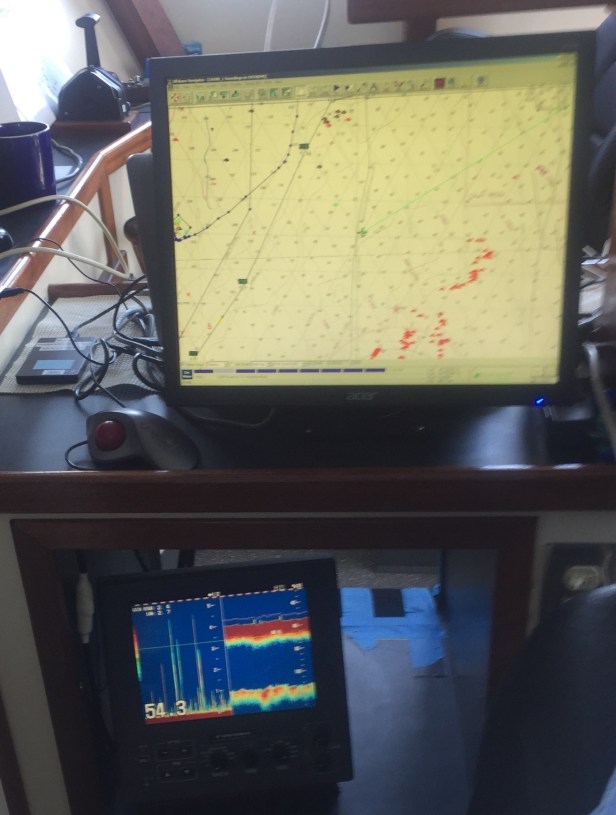

In practice, the method works best in “trawlable habitat”—areas where the sea floor is known to be smooth enough to avoid either damaging or losing the net, or picking up unwanted rocks and debris. On the US West Coast, many areas known to fishermen are trawled repeatedly and productively. A blog post that our field party chief Aaron Chappell wrote during last year’s groundfish survey describes the equipment, experience, and shared data that fishermen rely on to identify ideal locations for bottom trawling in order to fish productively and sustainably.

According to the United Nations, marine fisheries provide employment for over 200 million people, serve as a primary source of protein for an estimated 3 billion people. and generate as much as US$3 trillion in GDP globally.

The good news: Collaboration between fishermen, scientists, and conservationists could make it possible to meet demand for desirable groundfish species while managing the impacts of bottom trawling. Research conducted from 2009-2012 by The Nature Conservancy and California State University Monterey Bay Institute for Applied Ecology studied the impacts of repetitive trawling in conditions common along the California coast. The Central Coast Trawl Impact and Recovery Study found that increasing the intensity of fishing in a known trawlable habitat did not produce a corresponding increase in intensity of impacts. These results imply that bottom trawling in California (and other regions with similar characteristics) could be concentrated in known productive areas while additional critical habitat could be protected.

Today, the California Groundfish Collective also helps fishermen to securely share catch data in real time to help each other avoid inadvertently catching threatened species, even outside protected areas.